by Jay Edidin (as Rachel Edidin)

This article originally appeared at Playboy.com under the title “One of the Original X-Men Is Gay – And It Matters More Than You Think”; reposted with permission. Special thanks to Marc Bernardin.

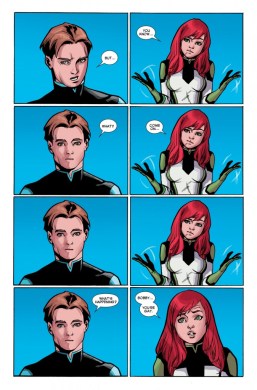

If you’ve been online in the last couple days—and especially if you follow comics— you’ve probably heard the news: Earlier this week, The Advocate posted a handful of leaked pages from All-New X-Men #40, out today from writer Brian Michael Bendis and artist Mahmud Asrar, in which a time-displaced teenage Iceman comes out as gay.

To understand why this is such a big deal, you need to know a little bit about the X-Men. This isn’t Marvel introducing a new queer character, getting accolades for diversity, and then quietly shelving them (Remember America Chavez?1) Bobby Drake — Iceman — is one of the OGs of one of Marvel’s biggest lines, a character with 50-plus years of cross-media name recognition. There’s a generation of kids who know him from the movies; another who grew up watching him on Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends. If this sticks — which it seems likely to, at least until the upcoming Secret Wars2 event tosses an immersion blender into the Marvel Universe — it fundamentally changes the landscape of queer visibility in superhero comics on a scale no other character’s coming out has.

That this is happening in an X-title is also significant: the X-Men have a large, dedicated, and markedly diverse fanbase; one that tends to be particularly attuned to representation of minority issues. There are a couple reasons for that.

That this is happening in an X-title is also significant: the X-Men have a large, dedicated, and markedly diverse fanbase; one that tends to be particularly attuned to representation of minority issues. There are a couple reasons for that.

The X-Men themselves are outsiders; and their outsider status is fundamental to their core premise, even when they’re not being written as a direct allegory for a specific marginalized group. As a teenager, I gravitated to the X-Men not because they offered a pointed metaphor for my sexual orientation, but because I identified with their liminality. The X-Men are superheroes for the rest of us — superheroes whose relationships to their powers and identities are often painful and fraught, superheroes who operate on the margins of both genre and society because of who they are.

But there’s been a consistent gap between what the X-Men represent in theory or allegory and whom they represent in practice. They’re used with striking frequency as a direct and obvious proxy for sexual minorities — but at the same time, within their stories, queerness is almost exclusively relegated to allegory or subtext (Storm, Shadowcat). The few openly queer characters in the franchise (Anole, BLING!, Karma, Rictor, Shatterstar) rarely make it further than bit roles. The most prominent openly gay X-Man is Northstar, a B-list character whose primary association is with a different team and title.3

So, while representations of queerness and coming out in superhero comics matter across the board, they matter a particular lot — and draw (and deserve) particularly close scrutiny — in X-Men. And the conversation around Iceman’s coming out has been, pardon the pun, more than a little heated.

Of course, the catch is that if we’re going to have a serious conversation about this story, we’re going to need to delve into two of the most complex and controversial fields: sexual orientation and identity; and X-Men continuity.

Fasten your seatbelts.

I saw the All-New X-Men pages a few minutes after they went up. When you co-host a podcast about X-Men continuity and write a lot about diversity and representation in geek culture and media, that kind of thing goes up like a Bat-signal. I read the pages, liked them a lot, and then stepped back to look at discussion as it rippled outward across social media.

The first set of responses came from a crowd that is mortally offended that Bendis has “made” an existing character gay, and they deserve the least attention of the lot. People come out as adults — including older adults — all the time. When you live in a society that treats heterosexuality as the norm and varyingly violently stigmatizes deviation from that norm, the pressure toward not only secrecy but denial is incredibly high.

Also, hiding your homophobia behind a veneer of cherry-picked concern for (alreadyconvoluted and self-contradictory) continuity is odious, and it makes the rest of us continuity wonks look bad. Don’t do that.

The second train of conversation that I’ve been following is less clear-cut, and — I think — more important. See, the Bobby Drake who comes out in All-New X-Men#40 isn’t exactly the one we’ve been following all these years: He’s the 16-year-old version of the contemporary adult Iceman, who, along with his teammates, has been pulled forward in time to the present.4

The second train of conversation that I’ve been following is less clear-cut, and — I think — more important. See, the Bobby Drake who comes out in All-New X-Men#40 isn’t exactly the one we’ve been following all these years: He’s the 16-year-old version of the contemporary adult Iceman, who, along with his teammates, has been pulled forward in time to the present.4

So, there’s another, older Bobby Drake running around the present — the Bobby Drake this one would have grown up into had he not been displaced from his own timeline — one who thus far has exclusively dated women, albeit not particularly successfully; and does not identify as gay, at least not publicly.5

This leaves a few possibilities.

The first — and least likely, I think — is that the adult Bobby Drake is exclusively straight. This is the possibility that has people, justly, concerned about the potential for erasure of a rare headlining queer character, and the fictional reinforcement of the idea that queerness is a phase or something that can be overwritten with abusive and ineffective practices like conversion “therapy.”

Based on statements from both Bendis and Marvel Editor in Chief Axel Alonso, it seems profoundly unlikely that Marvel will take this course. While their history on queer representation is pretty spotty, the company seems to be at least beginning to understand the value of representation and inclusion at a deeper-than-superficial level. From a more mercenary perspective, I doubt they’d want to deal with the inevitable and significant backlash that move would prompt.

The next possibility — and the one that seems the most likely — is that the adult Bobby is gay and closeted or in denial. That would be fine.

But there’s a final option — one that’s been largely overlooked — which is an adult Bobby who identifies somewhere else on the spectrum. And, honestly, that’s the Bobby I’d most like to see.

The emphasis on sexual orientation as fundamental and immutable — while a politically valuable one for pushing back against stigma and socially compulsory heterosexuality — is, I think, a damaging generalization. It’s not fundamentallywrong; there are a lot of people who are one thing, and always that one thing, and that’s fine, and important to recognize. But there are also a lot of people for whom sexual orientation is not a simple journey with a static endpoint; and I would love to see a comic that recognized and validated that as well. Who we are, how we identify, whom we love, and how we interact with and label those things are often mutable. My sexuality at 32 overlaps significantly with my sexuality at 16, but the intervening decade and a half have been an ongoing lesson in mutability, growth, and self-knowledge; of the relationship of experience to both desire and identity.

The emphasis on sexual orientation as fundamental and immutable — while a politically valuable one for pushing back against stigma and socially compulsory heterosexuality — is, I think, a damaging generalization. It’s not fundamentallywrong; there are a lot of people who are one thing, and always that one thing, and that’s fine, and important to recognize. But there are also a lot of people for whom sexual orientation is not a simple journey with a static endpoint; and I would love to see a comic that recognized and validated that as well. Who we are, how we identify, whom we love, and how we interact with and label those things are often mutable. My sexuality at 32 overlaps significantly with my sexuality at 16, but the intervening decade and a half have been an ongoing lesson in mutability, growth, and self-knowledge; of the relationship of experience to both desire and identity.

My experience as a queer teenager and a queer adult are not universal. That’s the point.No one’s are. And when the politically expedient party line, that sexual orientation is static and innate, carries over into fiction, it does a massive disservice to the many, many kids for whom it is not and never will be that simple; who struggle with their identities without the benefit of seeing their journeys reflected in media.

The third conversation around Bobby’s coming out has to do with the leaked scene itself — or what little we’ve seen of it, in a handful of leaked pages from All-New X-Men #40. And the reactions to that — at least thus far — have been the strongest, and the most radically divided.

For what it’s worth: I really like this scene. I like it as an X-Men fan; and I like it as a queer adult who used to be a queer teenager. As I wrote above, my experiences and perspective aren’t universal. I am not Your Magical Queer Friend™ whose approval means you can blanket dismiss the complaints of people who disagree with me. Clear? Good.

But I do want to address some specific points of pushback: about coming out; about bi erasure; and about the larger narratives that this is part of, fictional and cultural.

This is where I’m going to stop and talk a little about X-Men continuity; because these pages have mostly appeared stripped of their narrative context, and I think that narrative context of this scene matters a lot. When you’re looking at the leaked pages, you’re looking at a very small excerpt of a very long, serial story, which is the context in which most readers will encounter them. All-New X-Men has been running for a little under four years and it’s tied to characters and continuity that — in some form or another — go back to 1963.

Here are a few points of backstory:

The kids on these pages are Jean Grey (Marvel Girl) and Bobby Drake (Iceman). They’re both around 16. That’s relevant. Do you remember being 16? (Are you currently 16? Do your parents know you’re reading Playboy.com? High five!)

Bobby and Jean have been pulled forward in time, along with the rest of their team (Cyclops, Angel, and Beast, for those of you playing along at home). Because Marvel continuity runs on a slippery and inconsistent timeline, the comic has kept their point of origin deliberately vague. All we really have to go on is how the X-kids dress and the fact that one of them is shocked by the ubiquity of bottled water; which latter at least places them fairly firmly before the late 1980s. That’s also relevant.

After arriving in our present — her future — Jean abruptly acquired6 very powerful telepathy, which she’s been struggling to control with mixed success, under a mentor whose telepathic etiquette and ethics are — generously — flexible. That’s relevant, too.

So: Let’s start with the telepathy. Jean pulls the knowledge that Bobby is gay out of his head. If she went digging for it — as readers seem to be assuming — it’s a major violation of privacy. But there’s no textual evidence for that interpretation: As I wrote above, Jean’s control over her powers is shaky at best, especially when it comes to big stuff and people she’s close to.

What do you do when you stumble into a close friend’s biggest secret? Is it ethical to keep your knowledge a secret from your friend? There is no guidebook for this — especially when you’re coming into it with a cultural frame of reference that’s mostly pre-1988.

Here’s what we know Jean has to work with, based on the text:

She knows that Bobby is gay; or at least, at this point, attracted exclusively to men.

She knows Bobby is scared. That he thought he was going crazy — which he confirms.

She knows that they’re in an era where the repercussions and cultural context of coming out are much more forgiving than the era they came from.

She’s 16, with all of the arrogance and intensity that entails.

Here’s what we can reasonably assume, given the characters’ history:

Jean knows Bobby really well, even telepathy aside. They’re good friends, they’re teammates, and they’ve been through a lot together.

Jean has probably not had a lot of access to modern queer culture, politics, or literature. Where would she have encountered those things? Who would have thought to show them to her? Most of the relatively brief time she’s spent in the present has been dominated by jumping from crisis to crisis; in space or holed up in a paramilitary complex with strictly limited access to the outside world; fighting or running for her life. Her peers — the ones who weren’t pulled forward from the past with her — treat her like an artifact to gawk at. She’s been kidnapped. She’s been put on trial for the crimes of the woman she may or may not grow up into. And she’s been navigating her own identity crises, thrust into sudden and intimate contact with the most personal thoughts of strangers and friends alike, facing a future that involves her own repeated death. She probably hasn’t had a lot of opportunities to click around Tumblr.

This isn’t a callous monster. This is a 16-year-old kid trying her muddling best to be a good friend.

And guess what? She’s succeeding.

Look: Every article I’ve seen about this excoriates Jean for confronting Bobby the way that she does. Calls her irresponsible, presumptuous, harmful.

Look: Every article I’ve seen about this excoriates Jean for confronting Bobby the way that she does. Calls her irresponsible, presumptuous, harmful.

And look: They’re not wrong, at least not universally. “Face it, you’re gay” is not on the best-practices list — although, to address one specific point of criticism that left me seeing red, it is no more acceptable if you’re queer than if you’re straight. There are plenty of kids for whom this kind of confrontation would constitute a terrible and traumatic violation of boundaries. And yes, it’s important to talk about that, to say, “You should probably not do what Jean did.”

Except when you should.

Because here’s the thing: There is no one-size-fits-all coming-out narrative. We don’t often talk about this, the same way we don’t often talk about the fluidity of identity.

There is no one-size-fits-all coming-out narrative because there is no one-size-fits-all experience of sexual orientation. Or friendship. Because different people have different social needs and part of being a good friend is recognizing that. But there are kids — and adults — for whom hearing a frightening truth from a trusted friend is a huge and welcome relief: a signpost to a revelation; permission to acknowledge and articulate a secret they’ve been running from.

It’s possible to follow the best-practices list to a T and screw up. It’s possible to deviate from it and do just fine. Once more, with feeling: There is no one-size-fits-all coming-out narrative.

Let me tell you my story: Like Bobby Drake, I was 16. I was in a car with my mom, on the highway. This should be a red flag: as a rule, it’s a bad idea to start fraught conversations with someone who is physically trapped, or whose only escape is throwing themself out of a moving vehicle.

“Were you sleeping with [the girl I had been sleeping with]?” my mom asked. I said yes. “So, you’re gay? Or bisexual?” Another yes.

You will not find that script on the best-practices list, either.

But here’s the thing: My mom knew me really well. She knew that long drives were where we had always talked the most, and the most honestly. She knew that I was desperately and persistently independent, and that some of that reach for independence manifested as extreme secretiveness. She knew that it was very hard for me to tell her things that were important to me, especially personal things; and that I was very bad at recognizing which of those secrets could put me in actual danger.

And I was and am so grateful that she did what she did. Because I wouldn’t have told her on my own. I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that she and my dad would have supported me if I had come out to them unprompted, and I still wouldn’t have told them, no matter how badly I wanted them to know, no matter how badly I wanted to be able to talk about that part of my life with them. No matter how badly I needed their support.

It’s still hard for me to explain why not: My 16-year-old brain was a mysterious and frightening place, and time and perspective haven’t unraveled all of its mazes. My mom took a hell of a plunge — because my mom is a teacher, the kind of teacher it’s safe to assume does know those best practices. But more importantly, she also knew me. And ultimately, that mattered more.

Bobby’s discomfort is palpable in these pages; but, from where I sit, so is his profound relief.

All of that said: Don’t model your social behavior after a fictional character who can read minds. (Actually, don’t model your behavior on any X-Man, because X-Men is often a soap opera in superhero drag, and characters in soap operas make entertaining and dramatic choices, not good ones.) But do understand that coming out and navigating complex and often painful questions of identity is a different process for different people, and there is no more a one-size-fits-all approach to supporting them through than there is to coming out yourself. Just because Bobby’s story doesn’t look like your story — or isn’t the story you would want for yourself — doesn’t make it wrong.

And understand that denying the validity of stories that don’t align with those best practices is erasing the lives, experiences, and needs of a lot of the people you claim to be advocating for. My experience may not be universal, but it is far from unique; and it is a rare and welcome thing to see it reflected in fiction, because it is not how the story is supposed to go.

Then again, neither is being queer in the first place.

The other complaint that’s been bubbling up about the leaked scene is that it’s biphobic. Because no one postulates that the adult Iceman might be bi; because when Bobby offers, “Maybe I’m bi,” Jean responds that she thinks he’s “more… full gay.”

And again: I get where the pushback is coming from. Because biphobia is real and toxic, and a big part of it is built around the narrative that people who identify as bi are confused, or too scared to commit to identifying as gay. Those assumptions are used to dismiss and deny a lot of people’s identities. They’ve been used to dismiss mine. And it sucks.

But here’s the thing: We live in an aggressively heteronormative society (although somewhat less so now than in the nebulously pre-1988 era Bobby comes from). And when you have been raised in a culture that assumes you will be straight, and that often shows you only straight futures, coming to terms with being queer often happens by way of a series of incremental realizations. Of denials. Of bargains.

And sometimes one of those bargains is identifying as bisexual.

Sometimes it’s about identity politics and social stigma. Sometimes it’s about the fact that coming to terms with who you’re attracted to is often a different and less painful process than coming to terms with who you’re not attracted to.

Look: If a good friend — or anyone — tells you that they might be bisexual, you should not do what Jean does in All-New X-Men #40. You don’t get to make that call. You know this, right? This is not a roadmap for being a good ally.

Actually, Jean shouldn’t really get to make that call either — but Jean is also in a position to distinguish between honesty and bargaining that most of us aren’t. Sometimes that’s what being a friend means — and again, in this particular case, she’s better equipped to determine that than you or I will ever be. And look: I know that the interaction of telepathy and identity politics is not a topic that’s particularly germane to most discussions of queer theory and experience. But, as Bendis pointed out in response to a question on Tumblr, this isn’t most discussions of queer theory and experience. This is a story about a time-displaced kid from a less-tolerant era who happens to be friends with a telepath; and that telepath — like most 16-year-olds — is somewhat presumptuous and not particularly tactful. And there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all coming-out story.

So, no, All-New X-Men is not the story of every queer kid who ever struggled to come out. It can’t be, because we are a multitude of stories and experiences and truths that are often contradictory; because the sum of what and who we are is too varied and multifaceted to contain in a single narrative. This is one story, about two characters. And it will not reflect all of us, nor everything each of us hopes it will reflect, because this story is also about an experience that is widely variable and intensely personal, and to pretend otherwise is a disservice to the story, but more to each other.

All-New X-Men #40 isn’t my coming-out story. It isn’t yours. It’s Bobby Drake’s. And yes, sometimes it is uncomfortable to read; and no, it doesn’t toe all of the party lines, or model all of the best practices; and sometimes Jean is a jerk, and sometimes Bobby treats women in ways that are not okay. It’s messy and painful and complicated. And it’shonest.

And I wouldn’t change it for the world.

NOTES:

1. And Hulking, and Wiccan, and Lucy in the Sky, and Xavin, and Julie Power…

2. It’s worth noting that this is happening on the cusp of what promised to be major upset to the Marvel status quo, including the cancellation of nearly every ongoing title. (Then, again, that’s what they told us about Age of Apocalypse.) Whether Iceman will still be gay after Secret Wars is a question dependent on whether Iceman will still exist after Secret Wars; and whether, if he does, he’ll be remotely recognizable as the character he is now.

3. Northstar came out as gay in 1992, in a story that involved him finding a baby with A.I.D.S. in a dumpster. I am not making this up. Marvel then spent the next several decades alternating between using his sexual orientation as his primary narrative hook and ignoring it altogether until 2005, when they killed him off in three separate timelinesin the span of a month. (Later, he came back to life and married a nice man named Kyle.) Northstar is a rad dude — at least when he’s written well — but if he’s the most visible queer character in your entire publishing line, you have some representation problems.

4. If you think this is complicated, you should see the Summers family tree. There’s a reason my literal job is explaining X-Men continuity.

5. Not counting the time in Defenders #131 when he pretended to be Angel’s boyfriend to mess with a girl who was hitting on Angel.

6. This isn’t precisely accurate — Jean actually got access to previously existing telepathy that her mentor had been suppressing without her knowledge — but that’s a deeper dive than we’re going to take today.

I enjoyed the article and I think that these characters need to adapt to their environment as their stories progress. In the 70s, we had several black characters introduced, we had Spider-Man deal with both 9/11 and the election of President Barack Obama, and now we have IceMan coming out as gay. If these characters represent our modern mythology, they need to reflect the worlds they are in.

I completely agree. And when it comes to updating the world that the heroes live in, it does seem like Marvel is at least making a solid attempt.

Great read Rachael. I must confess that at first I wasn’t sure that I liked how Jean went about things. But you make very valid compelling points. This is really great. Thank you so much.

Fantastically written Rachel. You, as always, seem to have this great knack for summarizing X-men in a way that’s awesome, fun, and really makes you think.

The only problem I have with this the terrible dialogue between Bobby and Jean. It reads incredibly silly as if it was written by an old man trying to appeal to the youth, which it was. Felt that could have been done better.

Do love the outrage and tears by people who don’t even read comics though. That’s the best.

While I’m kind of indifferent on the actual specifics of bobby’s identity I actually really liked the conversation because it rings true to conversations I have had as a teenager. I’ve been both the bobby and the Jean here.

I like that Jean got stuff wrong because I’m sick of seeing only two types of teenage coming out stories in fiction: the ‘perfect’ with accepting peers who are are perfect and supporting VS the ‘nightmare’ with horrible reactions and slurs and violence.

In fact I think that often the reason the kind of conversations shown here happen is because straight peers believe that the choice to not come out to them is ONLY about fear of their reaction. Bendis seems to be trying to portray that coming out is as much (if not more) about struggling with how you see your self than it is about caring about how others will see you. I really appreciate that.

100% agreed, and beautifully put.

Agreed. My coming out had less to do with my peer’s reaction and more to do with my damnation. When I came to terms with my religiosity, no longer believing there were spiritual and eternal consequences to my earthly “sin”, coming out was easy (by comparison to the religious deconstruction I dealt with). And I love Bendis-speak.

An amazing article. The context is so important.

Thanks again for the article, Rachel.

I’m really excited to see the follow-up to Bobby’s story in Uncanny X-Men #600.

For me, one of the most important parts of doing reboots/retellings/alternate universe/time travel/etc. is that it provides an opportunity to look back and make things better, give some thought to some of the storylines that may be badly done or may have marginalized certain demographics. The fact that All-New X-Men has taken advantage of that opportunity by telling Jean’s story and showing Bobby coming out of the closet means a lot. I really hope that this continues. My one issue with all this has been that they keep interrupting the story with cross overs and stuff (some of which are good, some not so much) and I hope we get more continuous character development for them.

I think this is the best single take on this story that I have seen so far. Very interesting thoughts.

The reactions to this story have, naturally, been all over the place both with the revelation of Bobby’s character and to lesser extent but no less impassioned degree Jean’s role in it. With Jean Grey being my favorite comic book character period I wanted to chime in on the second part of that.

I’m happy with the way Jean was characterized in this story. I think most would agree that Jean didn’t go about this conversation exactly the “right” way, but I think that’s for the best. When you love a popular character you tend to notice the common traits voiced against them by those who don’t prefer the character. With Jean the most frequent words tend to be “perfect” and “boring”, both deplorable characteristics of the dreaded Mary Sue.

She definitely is not that here, and as Rachel said context is very important to understanding the interaction. Jean is obviously positive on these issues, but has little experience with them herself. Bobby is probably the first time she’s encountered them on a meaningful level, and as an eager caring teenager with the age expected lack of restraint of course she’s going to fumble it straight out of the gate, even though she means well.

It’s a messy confusing moment, just like life so often is no matter how we try to avoid it, and I think that makes it a much better story. If Jean had done everything the way she was supposed to, I feel this would have read less like a story and more like one of those stilted PSAs Marvel used to publish back in the day. I don’t know to what extent Bendis meant for this scene to come across this way, but even if you walk backwards into a good story by accident I say run with it.

You say that each coming out story is different. Yet I find your story and mine remarkably similar.

Thank you for the article. Now I can put my fears this event to rest

Great article. The best I’ve read about it so far, actually!

Thinking about this biphobia thing people are talking about, I wonder how much of this was Bendis (and editorial) trying to make sure this plot doesn’t just disappear once he’s gone from the book. Since he has just a few issues to wrap up his run, he won’t have the chance to actually get Bobby a boyfriend, for instance. So, by making the character bissexual, he’d be giving the next writers the opportunity to simply pretend nothing happend, and get Bobby a new girlfriend. Though we can’t be sure that was his intention without him actually saying it, we can at least be sure Bobby’s sexuality won’t be undone so easily.

Great article Rachel! I had pretty much the same conversation with my mom in a long car rides. Maybe trapping kids in cars is a parental tactic lol.

That actaully happened to me…

Great article, as someone who also had a messy, ‘imperfect’ coming out experience, it feels good to see a lot of how I was feeling about all of this expressed far better than I could have managed.

And I love your points about Jean. I’ve seen too many discussions about all this veer off into vilifying her and treating her so harshly for her actions, which given that she’s a teen-aged girl who’s been dealing with some pretty rough stuff since coming to the future, has made me a little uncomfortable.

My question is that I’ve never envisioned Iceman as gay, though apparently many people saw queer subtext in his actions through the years. What in his continuity supports this? The closest I could get was him dating Cloud (the Champion who gender swapped).

Personally, I hate what Bendis has done. I wouldn’t have minded and probably would have found it believable if not for the “full gay” declaration. If he was bi it would make sense then lil’ Ice could be like “Hey, why am I gay and your straight?” to Big Ice and he’d be like “Oh, I’m not. I’m bi. I’ve just been digging on girls mostly.” Then all of his continuity makes sense and he’s the happy well adjusted Bobby Drake he’s always been, instead of the closeted denier who has been living a lie his whole life to appear “normal” to his mutant friends and loving family.

Again–and I cannot emphasize this enough–plenty of people come out later in life. That narrative is perfectly true to a lot of real people’s real lives; your personal experience is not the be-all-end-all of what makes sense or is believable. What to you looks like a stretch is, for a lot of people, a perfectly accurate reflection of a reality and range of experiences that they rarely get to see expressed in fiction, let alone superhero comics. I’m kind of floored at the number of readers who will embrace retcons involving clones, cosmic doppelgängers, and alternate-timeline kids, but not someone coming out as gay in his 30s.

And the idea that Iceman being in the closet or denial about his sexuality means that none of who he is is real; that he can’t be–in most ways–the person he’s come across as strikes me as massively unfair.

And look, Iceman is a long-lived character in a company-owned shared universe. Over the years, he has been written by dozens of writers in thousands of comics; plus movies, cartoons, and other media. Those portrayals have not been consistent; given enough time, I can cherry-pick evidence–textual or otherwise–for pretty much anything I might choose to rationalize. The important part isn’t what can be justified by the text; it’s what makes a consistent and compelling story. Which this does.

(And all of the above said: I will trade that (already dubious as hell) textual consistency for wider representation any day of the week.)

I think it needs to be said that some people just think this is a bad retcon (not homophobia). I’d embrace the idea he was a clone, cosmic doppelgänger (don’t rule out that guy from the X-Factor Annual), an alternate-timeline version of himself,or at least bi with more ease than what has been presented. As you said Iceman “has been written wildly unevenly by dozens of writers over thousands of issues and more than half a century.” Iceman is my favorite X-man. For me, Iceman was at his best in the pages of X-Factor, I disliked a lot of what writers did to the character after that period and this just seems like more of the same inconsistency. There hasn’t been a writer whose done much good with him and I doubt this retcon improves things. I accept that some people value wider representation over the characters continuity, but I’d rather see a reboot than a retcon. For example, I’d really, really, really love to see a black Cyclops (the inner city orphan with uncontrollable destructive eyebeams), but I don’t want to see a retcon that could try to make it feasible in mainstream continuity (appearing white was a secondary mutation). I’m really hoping that post-Secret Wars 2015 we get all new continuity and an end to retcons (at least for a little while). Thanks for all you and Miles do ♥

He might well not know consciously. In the immediate aftermath of House of M, Bobby thoought that he too had lost his powers. It turned out instead that he had unconsciously managed to convince himself he was no longer a mutant, a deep telepathic scan by Emma Frost fixing that issue.

If Bobby is _that_ capable of convincing himself he’s no longer something that he knows he is, how much more capable would he be of convincing himself he’s not something he might never have known he was?

Well take his relationship with opal. Derided by his conservative father for dating outside the race then giving him the business about tolerance. Perhaps could use that as a one day coming out sort of? Maybe the point when frost used his powers more effectively than he ever did changed his view on things that it is okay to be vulnerable and put yourself out there?

God, I hate the word queer. Good article, but every one of those queers was like nails on a chalkboard. I understand the whole “reclamation” thing, but I think it fails. Maybe I’m just not radical gay enough to accept a derogatory term as a self-identity.

I appreciate your willingness to respect the terms by which I self-identify, as well as foundational and mainstream language in a decades-old field of theory, and part of an even longer established mainstream and primarily self-determined lexicon; and know that however you identify, and my personal feelings about those terms, I’ll afford you the same.

Trebligo, you refer to yourself as “not radical gay enough,” so I hoping I’m not jumping to a false conclusion if I assume that you are probably gay? And if you’re gay, you’re presumably comfortable describing yourself as gay. And good for you. Now when I was a kid, I heard “gay” thrown around as a dismissive insult a lot more often than “queer,” but obviously what I grew up with is not going to impact what you feel comfortable calling yourself.

Actually, it doesn’t have much influence on what I feel comfortable calling myself either, because I decided a long time ago not to let bigots determine what words I can use. However, there are other factors. As an adult, I don’t call myself gay because the word simply doesn’t fit. We’ve all agreed that “gay” refers to people who are attracted exclusively to members of their own gender. For those of us whose attractions are more complicated than that, and who may not even fit easily into gender categories ourselves, that word’s just never going to serve.

I love the word queer because it allows for a broader self-definition, a broader sense of community. Of course it’s also been in common usage in the academy for decades now, so it’s not exactly the fresh reclamation of young upstarts (nor am I all that young myself). Using “queer” in 2015 is not a matter of reclamation, frankly, it’s about using the best word we have to describe who we are. And obviously, if it’s not who you are, you have less reason to use it. But if your concern is avoiding language that’s regarded as derogatory outside the community, good luck with “gay,” because the teenagers of the last decade or two sure do love using that word as an insult.

Rachel, your entire argument is based on your own experiences; therefore it is is shaky. You cherry picked points without looking at the breadth of the character. You showed no logic dissecting the experiences of the character. The largest argument is his troubled relationships..this is a common thing with men in their 20s and women as well. I cannot prove this, but I am a teen therapist, and the way the coming out happened..wow very, well disgusting.

I will admit my own bias and disappointment, and that my response is somewhat emotional. Bobby was the average guy…got a job (accountant) and tried to make it. He was a lot of people. Bobby was kind of a normal joe. There are none of those in the X-Men, so it is sad to lose that. The X-men are an example of tolerance, they need an average guy with un-average powers to show everyone can work together. Every character does not need more layers, some can just be.

I will admit that this will bring/and has brought/ more exposure to the character, for that I am grateful. I believe your article is well intentioned, but please remember there is more than one way to interpret the character’s experiences because we read into the fiction our experiences. You saw repressed homosexuality, I saw stumbling everyman.

*love the work you two do, keep it up

We really went back and forth on whether to let this comment through moderation, but there are some things in here that I don’t think it would be ethical to let sit. So:

First: It’s really, really scary to see someone who counsels teens repeatedly present relatable normalcy and homosexuality as a binary juxtaposition. Iceman’s story–someone who spent a lot of their life deeply closeted–is incredibly common. Are “normal Joe” and “stumbling everyman” categories limited to straight people? Is that something you tell the teens you counsel? I really hope not.

Do you have any idea what it’s like to grow up with the only narratives of normalcy, of relatability, of successful or functional adult life inaccessible to you because of something innate to who you are? Shit like this is why the rate of suicide among sexual minority youth is epidemic, and seeing it from a mental health professional is incredibly disturbing.

Second: It sounds like a lot of what you value in Iceman is what’s commonly described as “passing privilege”–the ability to appear to pass as a member of a default mainstream while actually part of a marginalized group (so, in Iceman’s case, the ability to pass as a non-mutant). If that’s the case, I don’t see how being a closeted gay man conflicts with that narrative. If anything, it reinforces it: the conflict between membership in a minority group and the ability to pass as “normal” at the cost of having to conceal a significant part of yourself.

Third: It sounds like you understand how important it is to have points of identification in fiction, especially among the powerful metaphors and wish-fulfillment fantasies of superhero stories. You seem to put a lot of stock in continuity; are you aware that all of the original X-men have passed as human, held down regular jobs, and dated outside of the team? I mean: literally every single one. The set of characteristics you describe as so critical to Iceman–a set of characteristics which, again, I do not see as in any way incompatible with coming out as a member of a sexual minority–are common to the overwhelming majority of superheroes. Spider-Man. Captain America. Iron Man. The Incredible Hulk. Superman. Batman. Flash. Green Lantern. Green Arrow. If you want a “normal Joe”–by which you seem to mean a straight WASP dude who can pass as fully human, works in a white-collar job, and sometimes dates–you have your pick.

And you still begrudge queer readers one fucking character? Seriously? Seriously?

By the same token, do you think that little of straight readers–that they are so wildly and rigidly homophobic, so incapable of sympathizing with a member of a sexual minority that this one single characteristic will eclipse every other point of potential identification? That the times Iceman has gone full-on evil, been possessed, and a thousand other retcons and event horizons, cannot compromise this character; but whom he loves wipes away everything else of value?

Fourth: Let’s say this is really just a question of continuity. Am I cherry-picking? Sure, and so are you: We are talking about a character who has been written wildly unevenly by dozens of writers over thousands of issues and more than half a century. To appeal to continuity in that context is to cherry-pick. There is no way around that. That’s the beauty of long-lived characters and properties: their inconsistency translates to phenomenal narrative versatility.

Finally, as to your argument that the personal experience that informs my position strips it of its validity or value:

You are keying in on salient details that fit your personal biases and experiences, just as I did The only significant difference is that I was honest about it.

The fact that you speak for an overwhelmingly overrepresented majority does not make your position less subjective or more logical. It does not give you access to a higher truth. It just makes the stakes of caring about other people’s perspectives lower.

Which is something I’d really, really hope a teen therapist would understand.

Rachel,

Thank you for letting the comment through. I purposely invalidated my own argument by saying that there were emotions in mine. Problem with the internet is that emotions of words get lost, context,. This is why I will not post on the internet again. I just really appreciate the work you and miles do. I am not a WASP and have two aunts…I did not grow up how you presumed, but thank you for responding. My intent was to talk with someone who knows why this is an issue, and would delve into it, thank you for responding. Like I said, keep up the good work.

Rachel you may not be My Magical Queer Friend™ but this is the ‘definitive’ opinion-piece on ANXM #40, imo. Brilliant!

Hi, I just wanted to drop by to say that I really loved this article. I’ve been following the podcast for weeks now, and I just knew that Rachel would come up with the ultimate opinion piece on the subject.

Some time ago, when Miles Morales was first introduced and there was the same outcry from the closedminded fans, I wrote a piece (in portuguese) titled “Why we must give the mixed-race Spider-Man a chance”. This time I can just link people to your article: it sums up perfectly what I think about the whole thing, and adds a lot more!

I am less interested in the Jean backlash. Having spent the past two decades spending more time with my theater family than my actual one, I’m very accustomed to that very direct sometimes tactless way people can go about addressing sexuality because that tends to be a very tight-knit community that lionizes social transparency at least among ourselves. The X-Men are like that two with specific combinations of characters or branch teams having that same level of intimacy with each other that they can bypass socially appropriate niceties without it being treated like a violation. Granted, Jean telling Bobby he isn’t bi, he’s “full gay” does rub me the wrong way a little.

As a student of gender theory I think there’s more meat on the proverbial bone with the bi erase argument than anything else. I’m a little more torn because I approach it from at least two different angles. While I do subscribe to the notion that sexuality exists in a continuum and is in a state of flux throughout our lives (which comes into conflict with the LGBTQIA’s other arguments such as genetics or that it’s set in stone by developmentally at an early age), I won’t sit here and pretend I’ve never uttered the expression, “bi now, gay later.” And to an extent, I do think the phrase has a meaning if not outside the notion of sexual fluidity then at least correlative to it. I do believe that there is a certain percentage of gay males who at least when initially coming out will identify as bi because they’ve been socialized to conflate homosexuality with a lack of of masculinity, thus “bisexual” becomes a label which diminishes the impact of that stigma. I’m not saying all young boys identifying as bi do this, but like you said there is no one-size-fits-all coming out story. I’d also like to see the a story where the “bi now gay later” vs sexual fluidity arguments get explored/deconstructed.

While I can appreciate that some people may find this to be good representation (and certainly don’t begrudge them that), I find the argument that this scene is both poorly written and poor representation fairly compelling.

I’ll post excerpts from the arguments I read on this scene below:

“The key problem is that, even though agency in characters does not actually exist, Bobby is given no opportunity to figure out his sexuality for himself. It is defined to him by Jean Grey, who acts as some kind of arbiter of who he is for him, apropos of nothing, while constantly invading his privacy.”

[spacetwinks.tumblr.com/post/117020295616/man-is-there-stuff-saying-bobby-has-to-be-bi-or]

[Agency in Fiction: spacetwinks.tumblr.com/post/117256328541/kind-of-a-broad-question-what-do-you-think-it]

To be clear, the scene “makes a character’s sexuality wholly determined by another character’s analysis of them instead of that character’s exploration of the self.”

[spacetwinks.tumblr.com/post/116991831866/prepares-self-for-comic-sites-reporting-on-the]

Basically, there’s a critical, salient part of the queer experience in a heterosexist society – the negotiation of one’s own identity with broader social expectations, and one’s desire to conform to/internalization of broader social norms. And this scene elides that whole process.

I’m not saying this negotiation of the queer experience is necessarily universal, rather that it is typical, and I’m partial to the argument that representation that ignores this is shallow representation at best.

And further, it present Jean’s actions as an uncomplicated, unalloyed good. Basically, Bobby’s positive reaction reads as a narrative endorsement of Jean’s actions. His quick acquiescence and positive response – his relief – to Jean’s intervention is more about making the readers like Jean than about honestly exploring how Bobby would respond to such a confrontation, even if it was coming from a ‘good friend.’

The sheer presumption of this invasion of privacy and subsequent attempt to negotiate someone else’s sexuality seems underplayed, for the sake of convenience. Making that complex negotiation of identity convenient seems a bit dishonest, especially if this person is defined as coming from a highly heterosexist culture and unready to accept a queer identity; those seem like the exact conditions likely to produce a very complicated, inconvenient reaction to direct confrontation.

Certainly, there are people who would have such a positive reaction, but like the Rogue/Black Widow scene, this scene appears like it’s geared more towards the audience – making Jean relatable and providing a feel-good, pro-queer moment – than really exploring queerness.

I’m thinking back to the Wolverine/Nightcrawler scene in the Brood Saga, and comparing that instance of mutual respect of difference and camaraderie with this one. If Jean had just told a character she knew they had lost their faith and got them to accept their atheism in an issue, I could see how a lot of religious people would find that offensive and would consider that poor storytelling.

It’s not taking a complex situation and trying to address it with haiku-like elegance (something which you’ve noted is often necessary in comics); it’s attenuating an emotionally fraught experience to a degree that’s disrespectful to people dealing with the situation in their own lives for the sake of making the content digestible for an audience that, overwhelmingly, will not deal with that unique situation.

You may need to simplify issues for time and space, but at a certain point, you oversimplify the situation and rather than educating the audience, you’re now misinforming them. Basically, this scene feels disrespectful of the magnitude of the issue it’s dealing with by presenting such a pat resolution.

I don’t see this as a ‘pat resolution’ – all we’ve witnessed here is O5 Bobby’s 1st baby-step in coming out to 1 friend. It’s not a neatly wrapped-up 1-off vignette, there’s more to come per Bendis’ statements. It may well happen that we who’ve voiced our approval of ANXM#40 will have cause to change our tune but for now I think you’re jumping the gun & imposing a rather dry, scholarly reading to it that misses a ton of character- & X-specific context & subtext. Many of us who identify as gay go thru a period of protesting that we are bi – and NOT an authentic, positive expression of bi-sex identity but a societally-imposed, shame-based, last-ditch protest that we are “still at least 50% ‘normal'”. Jean’s bit of psychic shorthand here doesn’t define Bobby’s thoughts & feelings for him, it enables him to be honest about them. You can argue this removes his agency by f-fwding thru that denial-stage of his journey out, but that dismisses the context that these are time-displaced teens in the unique position of having confronted the failures & disappointments (& deadness, in Jean’s case) of their adult selves – their situation is fraught with a time-is-precious/fight-the-future aspect that makes this not so much a negative skipping-over of Bobby’s self-discovery but a uniquely honest & uniquely X-Men path to self-acceptance

I disagree with your analysis, but I can’t disagree with how you feel. I’m taking a ‘dry’ approach to avoid any arguments that sound like I’m saying people are wrong for liking this, because that’s not what I mean or even something that can really be argued.

First, this is not ‘Bobby’s 1st baby step;’ it is Jean’s shove. She’s not giving him short-hand – notes on behavior she’s noticed, language and observations he can reflect on – but presenting a conclusion and cornering him into accepting it.

He’s not coming out, he’s being outed (albeit to one person). It’s not a car ride conversation, it’s having your IM chat logs discovered (oh, the 90s) – but more invasive by several orders of magnitude.

An effective analysis must grapple with Bobby’s real lack of agency here, including the impact that has on this specific interaction (being unable to conceal his thoughts, to formulate their expression, or to lie), and how essential that agency is to the formation of identity.

Rather than have the character explore, define, and refine his identity – have him decide whether a bi identity accurately reflects who he is or is merely coping mechanism to try to negotiate (interalized) heterosexist expectations – so he can fully accept himself, this identity is foisted on him from without. Even if Bobby were to ultimately accept that identity, having it pushed on him should inspire more resistance.

The naming of our feelings and experiences is an intimate and inextricable part of those experiences. Being denied the ability to describe your own feelings can be as disempowering as discovering the words that fit your feelings can be empowering (“There are words for what I am?” versus “No one is really bi.”). Any scene that presents that denial as helpful and without negative consequence – that minimizes real world problems and avoids complex narratives – is suspect.

As a rule, I disagree that it’s possible to ‘jump the gun,’ because we’re talking about this scene, not any future arc. Countless solid/bungled scenes are ruined/redeemed by future developments, but that has nothing to do with the merits of the original scene.

Other writers may allow Bobby more time to explore and define his identity, but the glibness of the scene and seeming finality of its conclusion – “I’m not gay” to “I’m totally gay and cool with it” – makes me less confident.

There may be character specific reasons why this interaction would go this way, but you haven’t mentioned them. The degree of violation of privacy and the sensitivity of the personal information would suggest a less amicable conclusion, or at the very least, a more gradual process. Without more background, having a character acquiesce to being disempowered seems inauthentically convenient.

Pretty much any time a super-power conveniently solves a personal or social issue, it comes across as dishonest – a naive or otherwise unrealistic simplification. Privacy violating powers should probably create more trust issues than they solve.

Even if we assume Bobby & Jean share a healthy and intimate pre-existing relationship, Jean’s new telepathy – even if it’s involuntary – creates a huge power imbalance. This imbalance would likely be a major challenge for any adult relationship, let alone an adolescent one, and that challenge should be explored rather than treated as a non-issue.

Oh, and I just listend to episode 55. Pushing people to personal growth the haven’t earned through lived experience?

I saw this and wanted to comment.

“His quick acquiescence and positive response – his relief – to Jean’s intervention is more about making the readers like Jean than about honestly exploring how Bobby would respond to such a confrontation”

Why?

Bobby and Jean both agree that, up until now, he was going through such significant distress as to think that he was crazy. Having gone through such a situation myself, I can attest to the reality that this is not a good state for anyone to be in.

After Jean’s intervention, Bobby now knows what’s going on; he can be reasonably sure that he has the explicit support of a friend; he has been told that, in his environment, it’s fine to be whatever. He’s in a much better position to be able to do something, in marked contrast to his vexed and apparently unhappy older self. Isn’t it entirely plausible that one reaction of Bobby to Jean’s intervention–a dominant one, even–might be gratitude?

Please don’t moderate the comments too strictly. I respect Jc for having the guts to write something besides “You go girl!” I didn’t see any threats, profanity, etc. in his post. If you don’t like what he has to say, ok, but you shouldn’t silence someone because of it,

I decided to look back on this thread, and just wanted to say thank you.

Late to the conversation, I know, but I wanted to share a couple things. I’m really grateful for Rachel’s post and the courage and candor of the subsequent comments. I’m glad you let JC’s comment through too because even though I didn’t agree with it, I really valued the discourse.

When I first read All New X-Men #40, I found myself really frustrated with Jean’s role in Bobby’s outing. It did feel like a violation of the privacy of his thoughts and of his agency. At the time I could only really see my frustration with Jean. In reading Rachel’s post and the comments shared here, I’ve come to realize that while I relate to both Jean and Bobby’s roles and experiences in the issue, I have been a Jean more often than I’ve been a Bobby. I’ve come to the conclusion that my frustration with Jean is really more a frustration with my own tendency to “out” people (never related to sexuality). I have a bit of a reputation for asking questions that really dig deep into the person’s thoughts, feelings, and actions. I kind of push them to be upfront about their real motivations. I only ask the questions after some serious rapport has been built and I genuinely do it to benefit the person (or at least I thought I was). I’m beginning to realize that there is real value in letting people come to their own conclusions on their own timeline.

Ironically, I’ve had people push me on my own sexual identity and even now as a full-grown adult I’m still not as upfront as I could be about my identity. Maybe that makes me closeted or maybe that makes it none-of-your-damn-business ;). Either way, I think the story needed to be told for it’s benefit to both the Bobby’s and the Jean’s in all of us.

Coming from a little more than 3 years from this being written I have a lot to say.

First and foremost this was a great and interesting article to read. Second after the past few times thinking about this that in my original opinion this sloppy retcon to one of my top three favorite X-Characters, number 2 being Beast and number 1 being Cyclops, I initially didn’t like it mostly for how it treated one of my favorite characters. But in the time since it happened and a combination of both the older Iceman Scene in Uncanny X-men #600 and listening to to the podcast and reading some other articles I came to realize my problem with this retcon to Iceman is not that it happened but how I read personally read the time-displaced Iceman scene versus the older Iceman Scene from Uncanny X-Men #600. In my read of those scenes i personally feel time-displaced Iceman didn’t get a chance to admit it to himself in the same way older Iceman does i just feel that as how the scene is written is that its time-displaced Jean is telling time-displaced Iceman that he is gay not for example asking a question and through discussion let time-displaced Iceman reveal that he is gay himself like with older Iceman. Which i believe would have allowed the scene to come across better with long time Iceman fans like myself. And finally I’d like to add that despite this reveal Iceman is still my third favorite X-Men character especially since it didn’t fundamentally change what i love about and related to him the most. Which is that at the end of the day he’s still the emotional core of the O5 X-Men and the current X-Men Team like i tried to emulate in my own life.